Search here

Newspaper

Search here

Arab Canada News

News

Published: July 20, 2022

Inflation in Canada continues to rise despite Bank of Canada's efforts to limit price growth, as some economists and the central bank governor expect a higher reading in the June report scheduled for Wednesday.

Inflation, which reached an annual rate of 7.7 percent in May, has exceeded Bank of Canada's estimates during the first half of 2022.

For his part, Tiff Macklem, who holds the top position at the central bank, told a group of business owners last week that inflation is likely to exceed 8.0 percent in due course.

On the other hand, Bank of Montreal (BMO) said in its updated inflation forecast earlier this week that it now expects average inflation to reach 8.3 percent during the third quarter of the year.

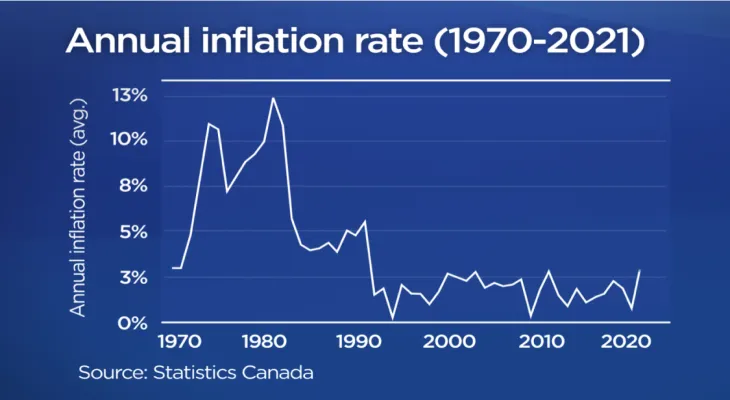

This took more Canadians of a certain age back to the seventies and eighties, when annual inflation reached 12.5 percent in 1981.

At that time, Bank of Canada had to raise its benchmark interest rate to 21 percent to regain control over prices, leading to the deepest economic contraction since the Great Depression.

On the other hand, experts told local media that there are some striking similarities between today's inflation episode and the price pressures that prevailed 40 years ago - as well as some key factors that could mean the difference between a recession or achieving the "soft landing" targeted by the Bank of Canada.

A striking similarity where James Orlando, chief economist at TD Bank, first began tracking similarities between the current inflation period and the peaks experienced by the previous generation in April.

He then pointed out that the causes of today's inflation - rising food, fuel, and shelter prices - were the same forces that drove Canadian prices higher over two different periods, one in the early seventies and the other later in the decade, extending into the eighties.

Explaining, "Current inflation is very similar to what happened at that time."

For example, many economists point to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the indirect effects on oil and food supplies as a primary source of global inflation today.

Also, in the seventies, the Yom Kippur War, followed by the Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War, placed enormous pressure on oil prices.

Meanwhile, meat prices rose by 70 percent in 1978, according to Orlando's analysis, leading to higher costs in ready-to-eat foods that may seem familiar to many Canadian households looking at grocery bills today.

Orlando wrote again in April that while price increases today may not be as large as those in the seventies and eighties, people may feel them with the same significance.

He explained that when inflation hits the essentials we regularly buy at the grocery store, it triggers a more intense emotional reaction from consumers.

But while prices were high, Canadians were also spending heavily through much of the seventies thanks to rapid wage increases and low interest rates.

Ian Lee, associate professor at the Sprott School of Business, recalls working during that inflationary period at BMO, where he dealt with the bank’s mortgages in 1980. He says that in the seventies, it made sense to borrow rather than invest and buy later, because interest rates were low and tomorrow’s prices were expected to outpace any returns on savings and investments.

"Saving made no sense at all, so it created a real culture of spending and spending and spending, and borrowing and borrowing."

Many Canadians put their money into real estate investment, and this led to rising home prices as Canadians rushed to the market, which contributed to increased inflation.

Shelter was also the main driver of today's inflation episode, with rents now rising at the same time as rising interest rates make mortgages more expensive.

Also, the main differences between today’s inflation and seventies inflation seem to lie in labor market tightness.

The seventies and eighties witnessed stagflation - leading to slowed economic growth and higher unemployment rates despite higher prices.

On the other hand, today’s unemployment rate is at a record low of 4.9 percent.

Meanwhile, Macklem pointed to strong labor force readings as evidence that the economy can tolerate higher interest rate hikes, even as some economists warn that layoff decisions could follow if the bank is too aggressive in raising rates.

In fact, when Bank of Canada had to raise its policy rate above the 20 percent mark in the eighties, following the U.S. Federal Reserve in the “war on inflation,” the economic pain was severe:

Unemployment rose to 12 percent in 1983.

Explaining, the only reason interest rates rose at that time was that Bank of Canada failed to recognize the inflation crisis until it was too late - prices rose over more than a decade, compared to the sudden changes over just a few months we see today.

By that point, central banks worldwide had not primarily used their policy rates to address inflation.

Canada was also among the first countries to adopt inflation targeting as a mandate in 1991.

Although it is believed that Bank of Canada once again waited too long to address rampant inflation, today’s response is years ahead of the eighties response, as the longer you delay taking medicine, the worse the problem becomes, and the harsher the medicine gets.

Interest rates will not have to rise for “Lee projects” as they did 40 years ago, and Bank of Canada has responded in time to avoid double-digit inflation numbers. Orlando says that so far, Bank of Canada has maintained belief among Canadians and businesses that it will bring inflation back to target - an important tool in itself for keeping expectations in line and stopping high inflation from becoming entrenched. "Faith is still there. And I believe the inflation target contributes significantly to that."

Are we close to the peak of inflation?

In its forecast this week, BMO expected inflation to peak in the third quarter of 2022, then fall to an average of eight percent in the fourth quarter and decline steadily through 2023.

For his part, Tu Nguyen, economist at RSM Canada, told local media that there are signs inflation may peak this summer, but what determines that largely lies outside the scope of Bank of Canada.

Oil prices have shown signs of decline in the past month from their spring highs, and the harsh measures taken by central banks worldwide are supposed to weaken consumer demand and give supply chains time to catch up.

Nguyen warned that while global pressures have shown signs of easing, they can easily continue or even reverse course during the fall.

Explaining, "There is still a war going on, a lot of instability and geopolitical tensions, and a raging pandemic. And who knows what will happen on the global stage over the next six months."

Comments